CT No.35: I want to know how we're being optimized.

Now's the time to prove whether our tech is actually making the world a better place.

Content warning: I’m at the stage right now where anger and humor are helping me get by. This post harnesses the anger. If you’re not in the mood to feel angry, I understand completely. This might not be the post for you today.

The state of our optimized times

“You can only have one KPI for each campaign,” I tell clients, giving them the line I learned in optimization school.* “The algorithm can really only optimize toward one thing at a time. You can optimize toward conversions or engagement time. One or the other. One might affect the other. But you can’t have both and clearly define success.”

It’s a helpful framework for prioritizing: What’s most important to you? Because if you’re going to optimize using a computer, the computer is not really that smart and can only have one true north: optimize towards this one value, taking the other values into consideration, but prioritizing the one. Computers make choices to solve problems, but people define what solutions are the best. People say, “Computer, go toward that best outcome and keep this other good outcome too, but not if it damages that best outcome too much.”

If you’re working with an algorithm, you can optimize for:

Long-term engagement or immediate conversion

Subscriptions or reach

Number of people who receive COVID-19 tests or profits

That doesn’t mean that you can’t have both at the same time. You can! Algorithms take into account many factors, such as the Quality Score metric for Google Ads and the paid Google search algorithm. Quality Score measures contextual relevance to the keyword you’re bidding on. No matter how high you’re bidding, if the content of your ads isn’t relevant, then you can’t win the auction and your ad won’t appear.

But no one optimizes toward Quality Score. In optimization school,* we are explicitly told not to optimize toward Quality Score. We are told to optimize toward conversions, or conversion rate, taking into account cost-per-conversion. But really, we are optimizing toward profit: what combination of factors will make us the most amount of money in the least amount of time with the least amount of cost?

You can have both a good Quality Score and high conversion rates, but an algorithm can’t optimize toward both. You can optimize toward one, then the other. But, to a computer, and to our optimization-driven mindset, only a single destination exists: the one best answer. An algorithm sees the black and white that we’ve directed it to see and directs all its efforts toward reaching that as fast as possible, given the rules provided.

That’s why algorithmic optimization has been so popular. If we give an algorithm a destination, it will find the most efficient way to get there.

We call it Defining Success.

*For most people, optimization school is on-the-job training from some people who have MBAs and other people who have learned from other people who have learned from MBAs or read Harvard Business Review. I did not learn about optimization in my social science graduate school program. I learned about it at my job.

Strategy and the crisis optimization plan

That’s how all algorithmic content recommendation works, and that’s what optimization culture is: You’re optimizing for one outcome over another. You focus and concentrate on one goal at a time. Once one goal is optimized, you move to another goal, not losing sight of maintaining performance of that first metric you optimized.

In the past week I have thought explicitly in this reference: the goal is to stop the spread of a disease. If I, a gregarious person jaunting through Los Angeles touching surfaces willy nilly for a week, have somehow contracted this disease, and we are trying to stop the spread of the disease, should I really go into a tiny aluminum tube with a bunch of other potentially infected people and bring something back to my home state, which has not actually been as severely affected by this crisis as others? Am I Typhoid Mary? Which metric am I optimizing toward: my own comfort or preventing disease spread?

I stopped driving myself crazy with this decision and decided to go home, armed with bleach wipes and the conviction that it’s unlikely I contracted coronavirus. After all, I can self-quarantine far better in my own home.

So now that I’m here, I’m wondering: how is everyone else optimizing? And by everyone else, I mean the businesses that are still running smoothly.

Like, say, Amazon. How are they defining success in a crisis?

To start, both the WHO and CDC say that it’s unlikely the virus can be contracted through the mail, that most surfaces are safe, that it’s mostly human-to-human transmission and it’s unlikely the virus is transmitted through the mail or package delivery. (I want to help them optimize that information for organic search because it took a variety of queries to get the answer.)

It’s great that Amazon is “ending shipments of non-essential items to warehouses” so they can make more room for “essential” items. I want to know how essential and nonessential are determined by their algorithm. I’d like to have some visibility whether the buck-stop metric is a.) getting as many supplies to people as possible or b.) algorithmically optimizing toward making as much profit as possible while getting “essential” supplies to a lot of people. I don’t need to know how the entire operation works. I just want to know: what’s the KPI here? Are the pillars still “selection, price and convenience,” or have those changed?

We know, generally, how grocery stores prioritize space on their store shelves. How are Amazon’s product recommendation algorithms optimized: for health value? Availability? To prioritizing businesses that are treating their employees well enough that they aren’t spreading disease in their communities? (I doubt it.) If we know how grocery stores work, if we debate how grocery stores work in Congress, wouldn’t it make sense to know how our grocery delivery algorithms are optimized as well?

Amazon’s vision statement is “to be Earth’s most customer-centric company.” Clearly, that’s at the detriment of workers — and potentially the public good. Does that mean that they will ultimately optimize only to improving the lives of only the customers who can pay?

I’m picking on Amazon here (fairly, FWIW) and being a bit dire. I’m thinking about all delivery tech and supply chain optimization algorithms out there as well as the slide decks and decisions that went into them.

I want to know what those KPIs are in health care, too. At for-profit hospitals, where administrators and insurance companies are keeping needed beds filled with patients who might not need to be there anymore. At pharmaceutical companies, who before the crisis prioritized high-profit drugs over everyday supplies. At urgent care centers, which can’t seem to decide whose symptoms are worth testing.

I want to read the slide decks where they determine how KPIs shift in crisis.

As I hear all these stories — and thank God for the internet, very serious about that here, because keeping track in real time feels somewhat necessary this time around — I wonder: What’s the general KPI here?

Because to me, it’s clear that the KPI should be Prevent spreading the disease. Our secondary KPI, is Save as many lives as possible. Can our algorithms optimize for those?

Which systems are really optimized for the outcomes that matter?

There’s clearly a system that works, as both South Korea and China have significantly curbed COVID-19 spread. In the U.S., despite our deep resources and massive private supply chains, easy transmission of information, and commitment to the private sector above all, I wonder: how are we optimizing? Are we optimizing for public health or are we still optimizing for profits? How is the brilliant “make the world a better place” tech-enabled future we’ve been promised coming to fruition?

We’re very good at finding others to blame — pointing fingers at young people at bars, or side-eyeing anyone who coughs (I’m certainly guilty of this!) — when it’s clear that we’re the ones woefully underprepared for crisis. We’ve always defined success as profit margins or market success or jobs created. We’ve never defined success as ensuring that our quality of life is livable.

This week I’m thinking more about how I define success.

Maybe we should rethink how we’re optimizing our algorithms. Maybe we should keep asking, loudly, over Zoom happy hours, where are the tests we need?

Feel free to

if it makes you feel a little bit better.

It made me feel a little bit better to write the above.

Wouldn’t it be really great if I reviewed Zoom right now? Evidently kids are.

Helping make sense out of to-do lists amid hard times: Bella Scena

Admittedly: I’m lucky. My job’s been fully remote for almost a year, and I have a full plate. But like many of you, I’m having a hard time concentrating on anything right now. I’m easily distracted by my new feline coworkers and my relief at being home and my anger (see above) and desire to just not.

I don’t think that our culture needs to make this a “productive” quarantine. But I do appreciate working and the feeling of accomplishing something. It keeps me sane. However, I can’t work if I can’t focus on the task at hand. And what task is that? Bella Scena will tell me.

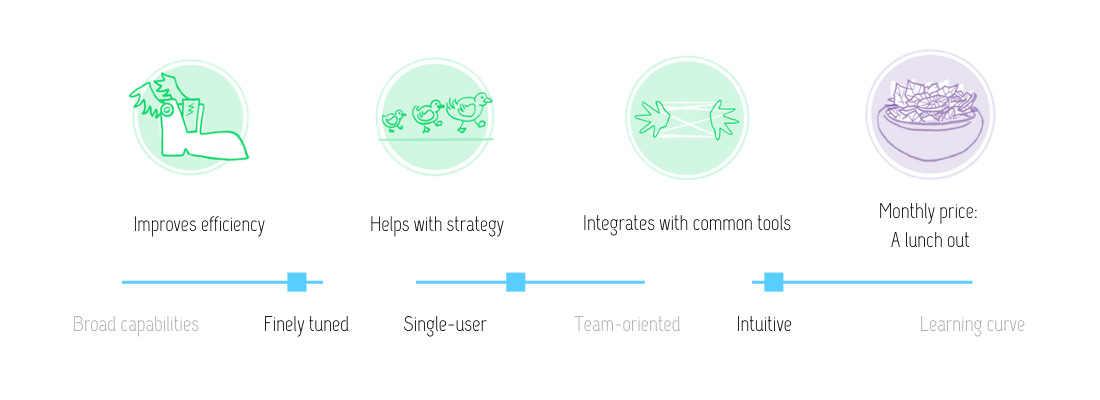

I’ve used Bella Scena for calendar and to-do list management for several months now, and swear by it. Its calendar integrations and to-dos that make me feel so accomplished and organized.

Full disclosure: Bella Scena was created by Wonderly Software Solutions. I met Bella Scena’s creator and Wonderly founder Amber Christian at an IA conference, and we’ve been friends since. Our friendship doesn’t affect the fact that I think Bella is awesome — I discovered Bella Scena through Amber, but I recommend it because I use it every day and enjoy it.

Bella Scena at a glance

Bella Scena has two primary functions:

It creates a to-do list next to your weekly calendar, then integrates with whatever calendar software you use

It manages meeting agenda and notes, including distribution to all parties involved.

Admittedly, I do not use the second function, as I’m a poor note-taker and just use AI transcription at this point. But the to-do list: oh my word, the to-do list! Bella Scena also features the ability to nest or group tasks and associate them with meetings — it keeps me organized. It has a WYSIWYG sensibility that mimics the feel of a paper calendar.

Bella Scena’s best feature is the “Take a Deep Breath” button, which essentially allows you to write out all the things you have to do in one fell swoop. The software then creates individual to-do items, which you can drop into your calendar to establish deadlines and workflow. You can add tasks to associated meetings.

Then, when you cross something off the list, the associated cross-off animation is incredibly satisfying. It mimics the satisfying of the pen-and-paper to-do list way better than the ol’ digital checkmark.

Bella Scena has team features as well, so that you can coordinate meetings and tasks with your team. It’s not a fully-featured project management app, though. It’s more or less a digital version of a planner — right down to the fact that it’s not super mobile-responsive, so I only use it while I’m working at my desktop.

But it’s a lifesaver now. It’s great to have a productivity app that reminds me to take a breath. Helps me get organized. Ensures that I can make sense of the chaos that is my to-do list.

A request for your links

Do you have delightful digital content apps, websites or experiences you’d like to share? Send them my way! I’d like to keep sharing the flow of awesome digital content experiences and innovations going throughout this separation from the outside world.

Next week: more on my website redesign process and the strategic brief outlines that were promised!

Visit The Content Technologist! About. Ethics. Features Legend. Pricing Legend.