Our billionaire-owned alt-weekly shut down this week, which is a major bummer. The billionaire could have saved it, but he didn’t, which is what happens when billionaires are in charge of media.

The U.S. elections are less than a week away, and I’m deep into anxiety mode, so forgive the cranky tone and slippery metaphors.

More excitement — and big news — coming next week, regardless of election results. In the meantime, this week:

Big, scary bad stats that can be really difficult to overcome

A review of screen recording software Loom

Content tech links of the week

Are you new here? You can

When big statistics lead to scary conclusions

Last week I was in a meeting where someone argued the following point as a case for maintaining high levels of personalization in ad tech: “70% of Hulu subscribers do not opt out of ads even though they option is available to them, and studies say 63% of people prefer targeted advertising.”

When I hear stats like these, which are usually repeated out of context with no sourcing, methodology, or dates, I freeze up. They’re often a red flag that nuance and design intentionality are going to go out the window in favor of “majority rule.”

Big stats are nothing new to marketing and business, and I’ve been known to throw around a few myself (although usually I’m also shouting “That’s what Pew says!” along with the data point). Statistics and data are fantastic to support an argument when they’re applicable to the conversation at hand.

Most of the time, however, the big stats are hot air. I’ve written before about the dangers of data we don’t understand, including:

how data early on in the pandemic was extremely unreliable and often misused

how our reliance on demographic data can contribute to racism and digital red-lining

In the United States, until this year, most of the data we regularly consume is related to our deeply flawed and fragile electoral system. Our grade school-level training in democracy and leads us to think that if we have a data point that proves more than 50% of people prefer X over Y, or there’s a plurality among three choices, we’ve won the election. There are no other choices; the winningest preference decides, no matter the externalities.

Building products and content for people is not a winner-take-all mandate. A democratic election isn’t even a mandate to ignore dissenting preferences, regardless of politicians and horse-race news coverage and all the rest. Unfortunately, our professional conversations in the age of data excess and growth hacking don’t often reflect our ability to understand complex narratives.

Data should never shut down reasonable dissent

Many of us hold dear the principles of accessibility, in which products are designed for as many people as possible, regardless of ability, circumstance or internet speed. In my interpretation, accessibility also extends to comfort and consent: if a significant number of people express concern about a major change or circumstance, especially one they can’t reasonably opt out of or control, keeping technology and media accessible and functional means listening to and incorporating those concerns into the larger conversation.

In the age of networked knowledge, the 20th century media strategy of “controlling the conversation” is used more as steamrolling the conversation. Statistics and data are used to shut down diverse opinions and preferences, rather than an opportunity to discuss how and why those preferences or reservations were formed.

If in a survey, say, 70% of people say they don’t mind digital advertising (which I can’t find support for anywhere, but I’m just using it as a Random Tech Example Stat), what are we saying about the 30% of people who do mind? Are their opinions valid?

If a plurality 44% of people say in an opinion poll that we should not reduce the size of our police force, then surely that makes the whole city’s opinions official. No matter that 40% said police should be reduced and 16% are not sure — no further discussion, the biggest number wins and the concept of police abolition won’t be discussed any further in the local newspaper. (The Minneapolis StarTribune did a great job of reporting the actual protests, but their treatment of police abolition that really sticks in my craw, especially this poll and its subsequent use as “proof” of anything besides a multitude of opinions.)

We use stats in communication as a winner-takes-all, even though they’re just a sampled probability. During the pivot-to-video years, video vendor teams kept throwing out the stat, “80% of all content consumed online is video” as justification for a video investment.

In some meetings, I countered that statistic with statements like, “While I’m a believer in a mix of content that includes video, that number is misleading. That statistic is that high because you’re counting streaming services like Netflix, where people binge-watch for hours at a time, in with the content they consume on social media and web.”

Cue the dagger looks.

Preemptively creating better conversations around data and statistics

I don’t have overt solutions for these big bads, these giant statistical vampires that suck all choice and nuance out of a situation. To be frank, I probably counter these statistics tactlessly at least 50% of the time. I’m either silent and muttering, or I’m loud and belittling. People don’t really like when you’re kneecapping their core argument for existence, and I haven’t found the right way to address it either.

But when we have the opportunity to use statistics in a presentation, maybe we can provide a little more context. Let’s not use individual statistics as a mic drop.

We can provide our own explanation as to why we trust that data, and even more information about how we interpret what it means. Some solid explanations might be:

The data is our own and represents the nuanced opinions of our readers, all of whose points of view are valid.

Example: Even though 44% of people said they want more food and drink content, we should also pay attention to the 15% that said they wanted more comics content.

The data comes from a reputable source, like Pew, the census, an established polling institution, or a research university with a large data set (aka not just the marketing “studies” grad students run with college sophomores as test subjects that prove nothing except the fact that sophomores at state universities are, well, sophomoric.)

The methodology by which the data was collected is sound, and a brief explanation of why those methods were used.

Example: Mention the number of respondents in the survey (n) or explain the study’s statistical significance.The data represents a legitimate gap — or a bigger world — that should be acknowledged.

Example: Did you know that 46% of the world’s population are not internet users, per the International Telecommunication Union (aka the UN). That doesn’t mean that because 53% of global citizens are internet users, we should assume everyone has access to or even wants to be on the internet.

The data is very recent and represents a change in opinion — even (especially) if it’s a smallish percentage that indicates a rising trend.

Example: a July 2020 Gallup poll found that 15% of Americans in 2020 support police abolition, but compared to the number that would have supported it in 2019 or the fact that pollsters are even asking about it to begin with… well, that’s something we should acknowledge.

The data represents a very limited of number of people using a feature or accessing certain content, unless that content serves a core need (like a specific form or a level of transparency like a privacy policy).

Example: Carl and Jim are the only ones who use the comments widget, which contains some unknown opaque tracking that may compromise privacy, so maybe we should get rid of the comments widget until we can assure the safety of all our users.Multiple high-quality data points build to a conclusion, rather than just one or two statistics from assorted surveys.

Example: If, just over one year ago, considering everything above, 73% of Americans believe that our political parties don’t agree on “basic facts” (Pew again), why are we using big stats to make our points to begin with?

Recognizing and addressing a diverse outlook — racially, culturally, and honestly we contain multitudes— means that we have to encounter and account for other points of view that may not easily fold into giant survey numbers or easy data points.

The only data that represents an election is actual election data. Otherwise, most big statistics have very little to do with actual people and shouldn’t drive blanket decision-making.

Data is be the starting point of a conversation and a guideline for benchmarking progress. It’s one of many weapons for change in our arsenal.

Encouraging more conversations, nuance, complexity about the data we see in marketing presentations, in product development, in news stories and everywhere will pay off in the long run. That’s my little hope anyway.

As a closer, here’s David Bowie presciently discussing the internet in 1999:

Just show me what you did real quick: Loom review

Do I miss when people look over my shoulder so I can demonstrate software? Not really, but in the pandemic era, I don’t have to worry about it anyway. However, instructive screen recordings have long been a bit of a pain, not necessarily to produce but to upload and send to your target audience.

Despite the rhyme, Loom has no connection with Zoom except that it’s a freemium self-service video platform that has recently risen in popularity. But Loom is quickly becoming a standard, shorthand name for quick and easy screen recordings.

And it’s a keeper! Since I’m not a fan of excessive Chrome extensions these days, Im happy to have the choice of Loom’s desktop software or an extension. Loom also has a really lovely Privacy for Humans policy on their website, which outlines data they collect and explanation for all the tools they use to run and analyze the software.

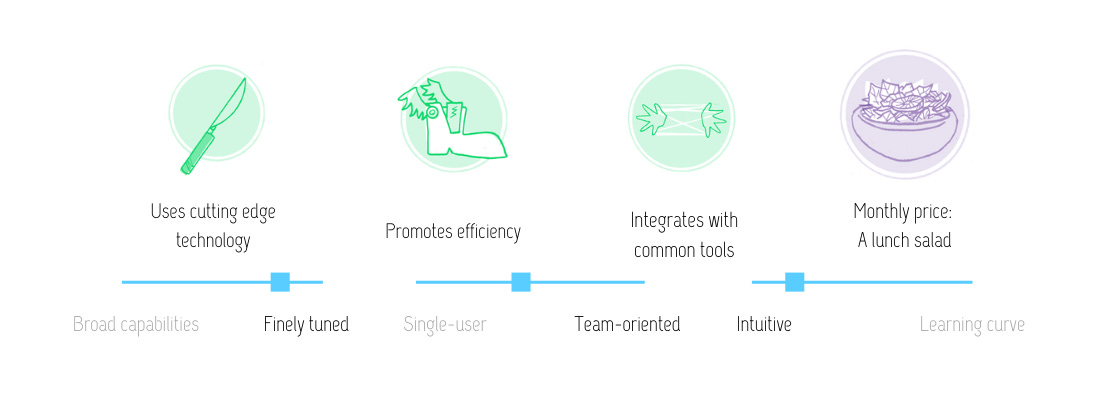

Loom at a glance

Loom records video and audio of your screen and is primarily used for software demonstration: using a new CMS, training someone on Google Analytics, etc. Its easy-to-use desktop software captures your screen and mic in tandem, then saves your video immediately to the Loom platform for editing and sharing.

The tools’s strength is in its extremely fast processing and sharing of these screen recording videos. Sharing a minute-long demo video directly with a client or embed in your help center is far easier than uploading to YouTube or a video hosting platform like Wistia. Those channels have their place, but Loom serves a more immediate, less produced need.

When you have bad takes, you have to go into the platform and delete them, but the casual, one-off nature of Loom means that your word flubs and ums and ahs are more acceptable, most of the time.

If you want to use your Loom videos elsewhere, you can download. Or, if they’re super amazing, you can make them public and indexable in Google search via toggle.

Loom’s low price point and extremely flexible nature puts it almost in the too-good-to-be-true category. Will it be purchased by one of the big tech players and or eventually become extraordinarily expensive? Maybe, but I’m not here to speculate on that.

For the moment, Loom is worth the low monthly cost of easy demonstration videos.

Content tech links of the week

Not a lot of substance this week; I’m probably missing everything.

New Google tech for reporters. I’ll check into it next week.

Ads on Substack: it’s a thing, of course. Via Digiday. Medialyte’s take on the same topic goes more in depth.

Why social media startup culture — especially Facebook — isn’t set up to fix the problems it has created, via The Information. I liked this take because it’s not just “Facebook bad”; the closing paragraphs give suggestions for how companies can be structured to better address societal problems in the

If I’m a vampire, an extended theoretical essay on media subculture is basically fresh blood, even if one of the subcultures it discusses is Phish. (H/T to Office Hours for linking this one.)

This concludes our spookyish October! Have a safe Halloweekend and if you’re in the U.S., please vote, even if you don’t want to because you’re tired of everyone telling your to vote.

Do you like this newsletter? Please

Visit The Content Technologist! About. Ethics. Features Legend. Pricing Legend.